Shaping a Nation Through a Song: The Story of “God Defend New Zealand”

by Nathan Shaw

An Inspired Poet

Thomas Bracken wrote the words of New Zealand’s National Anthem, “God Defend New Zealand.” The anthem is a heartfelt prayer, imploring God to protect and shape the nation. It is remarkably prophetic in nature. When Bracken wrote the poem he had no idea it would become New Zealand’s National Anthem. It takes only a short time to write a poem, it takes a lot longer to shape a poet. Bracken’s early life was shaped in a crucible that prepared him to release God’s heart for New Zealand. Sadly, his life is little understood in our generation.

Bracken was born in Ireland on December 21st, 1841 (his baptism entry is clearly dated December 30th, 1841). In the previous year two significant events transpired: Bracken’s parents were married (4th September 1840), and, in a remote nation on the other side of the world, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between Māori and the British Crown (6th February 1840). Bracken’s early life was marked by tragedy and difficulty. His mother died on the 8th of December, 1846, less than two weeks before his fifth birthday. She herself was only about 26 years old. From 1845-1849 Ireland endured a great famine caused by potato blight. Of a population of four million, one million died, another million sailed away in despair. A few years after the famine Bracken’s father also died (August 1852). Bracken was not yet 11 and his father was only about 41. For over three years Bracken lived with an aunt.

Bracken was born in Ireland on December 21st, 1841 (his baptism entry is clearly dated December 30th, 1841). In the previous year two significant events transpired: Bracken’s parents were married (4th September 1840), and, in a remote nation on the other side of the world, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between Māori and the British Crown (6th February 1840). Bracken’s early life was marked by tragedy and difficulty. His mother died on the 8th of December, 1846, less than two weeks before his fifth birthday. She herself was only about 26 years old. From 1845-1849 Ireland endured a great famine caused by potato blight. Of a population of four million, one million died, another million sailed away in despair. A few years after the famine Bracken’s father also died (August 1852). Bracken was not yet 11 and his father was only about 41. For over three years Bracken lived with an aunt.

Eventually Bracken was sent to a relatives farm in Australia. He arrived on the South Carolina from Liverpool, docking at Adelaide on August 7th, 1856. During his 13 years in Australia he worked in various employments. It was here, while working on a sheep station, that he began writing poetry. In 1869, aged 27, and full of idealism and hope, he immigrated to New Zealand, settling in the fledgling city of Dunedin. His poem “Dunedin from the Bay” reveals his first impression of the city as he sailed into the harbour. Bracken was deeply impacted—“O never till this breast grows cold, can I forget that hour.” God instantly imprinted Bracken’s new home land on his heart.

Bracken was both likeable and friendly. One contemporary described him as having a heart as big as a pumpkin. He connected easily with people, including people of influence. He didn’t, however, neatly fit the narrow religious and political moulds and expectations of the times, and was from time to time misunderstood. The Irish Catholic Bishop of Dunedin, Bishop Patrick Moran, was eager to start a Catholic newspaper. Bracken eagerly supported this endeavour, travelling on horse back to distant gold mining communities to gather financial support. He raised a very significant amount indeed and returned fully expecting to be appointed editor of the newspaper. Bracken was summarily dismissed when it was discovered he wasn’t a “practising” Catholic. The exact words of the Bishop were, “You are a heretic!”

Bracken later wrote about Bishop Moran in “Pulpit Pictures,” a collection of sketches of local clergymen. The sketch of Bishop Moran shows no signs of animosity. Still, the incident appears to have impacted Bracken deeply, and no doubt influenced his most reputed poem, “Not Understood.” “Not Understood” is achingly transparent and deeply insightful. One line in particular hints at Bracken’s sense of destiny and call: “The poisoned shafts of falsehood and derision are oft impelled ‘gainst those who mould the age.” Bracken knew that he was called to in some way shape and mould his age. He also knew the pain of “poisoned shafts” hurled by those limited by fear, prejudice and greed. “Not Understood” went on to receive notable international recognition.

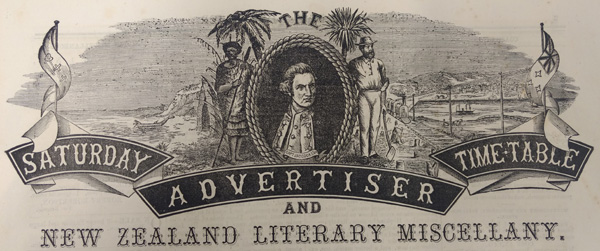

In 1875 Bracken found his niche as the editor of the Saturday Advertiser, a newspaper that he started with two others. The Saturday Advertiser was hugely popular with a, for then, very large circulation of 7000. At the time Dunedin had a fast growing population and was the biggest city in New Zealand (census data gives a population of 18,499 for 1874 and 22,525 for 1878). Bracken shone as an editor and wrote prolifically for the publication.

A quick perusal through the Advertiser reveals that Bracken was in touch with international, national and local scenes, and was a true influencer of culture, writing with depth, clarity and humour on current issues. The Advertiser quickly gained recognition around the nation. A review in the Southland Times in February 1877 noted that Bracken had, “already earned for himself a very honourable position as a New Zealand littérateur” and stated confidently that his Advertiser ranked “second to none in the colony” (28th February 1877).

On July 1st 1876 Bracken published his poem, “National Hymn,” in the Advertiser as part of a song writing competition. The blurb for the competition stated:

“National songs, ballads, and hymns, have the tendency to elevate the character of a people, and keep alive the fire of patriotism in their breasts.”

The successful winner would receive a prize of 10 guineas (about $NZ1500 in today’s currency). In 1877 the poem had pride of place in Bracken’s publication of poetry, “Flowers of the Free Lands.” It was still titled “National Hymn.”

An Inspired Composition

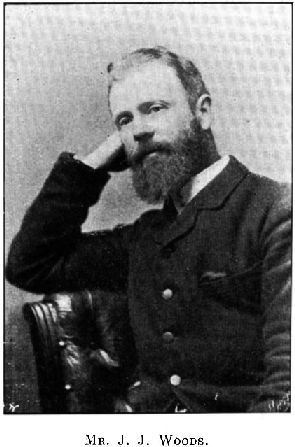

John Joseph Woods was born in 1849 in Tasmania, Australia, of Irish parents. He ventured to New Zealand as a young man and in 1874 became the head teacher of the Catholic School in Lawrence. Lawrence was a gold mining town 96 kilometres from Dunedin. Woods was also a choirmaster and musically gifted.  The mail coach, carrying the Advertiser with Bracken’s song competition, arrived in Lawrence at 9pm. It was a cold midwinter night. Woods collected his mail and a copy of the Advertiser. Recalling the events of that night Woods later wrote:

The mail coach, carrying the Advertiser with Bracken’s song competition, arrived in Lawrence at 9pm. It was a cold midwinter night. Woods collected his mail and a copy of the Advertiser. Recalling the events of that night Woods later wrote:

“On reading the beautiful and appealing words, I immediately felt like one inspired…I set to work instanter and never left my seat till the music was completely finished late on in the night.”

There were twelve entries for the competition. The entries were sent to Melbourne, Australia and judged independently by three judges. The results were published in the Advertiser on October 21st, 1876. All three judges selected Woods’ entry. Only in submitting his entry did Woods refer to the poem as “National Hymn.” In all of his correspondence after this he referred to it as “National Anthem.”

The first public performance of the song was at a grand sacred concert on Christmas evening at the Queen’s Theatre, Dunedin. There is no doubt it was a rousing performance. It was sung by the large Lydia Howarde Troupe (16 principal singers and full chorus) and accompanied by the Royal Artillery Band. The Advertiser mentioned that the performance “evoked very loud applause” and praised Woods’ for his “spirited composition” (30th December 1876).

The Battle to Get it Published

One of the rules of the competition was that the copyright for the winning entry would become the property of the Proprietors of the Advertiser. The Advertiser gave the song to Dunedin’s Charles Begg & Co for publication. For no known reason the firm did nothing with it for nine months. Eventually they sent it to a Melbourne publisher who dilly-dallied for another two or three months. When the printed manuscript finally arrived in Dunedin it was mangled and included only one of the five verses. The Advertiser and Begg’s both refused this edition. The Melbourne publisher agreed to reprint it but never did so. After a lengthy wait the Advertiser abandoned its intent to publish the song.

Bracken, quite upset by the whole affair, had a fiery exchange with Mr. Brown of Begg’s. In a letter written to Woods, Bracken referred to Mr. Brown as “a damned mean skunk.” Ultimately, however, this unfortunate series of events worked out for the best, primarily because Woods was all too eager to take over the assignment. Bracken obligingly relinquished the copyright to him. Woods wasted no time, and spared no expense. On the 16th of February 1878, 700 copies were printed by London publisher, Hopwood and Crew. It was an elaborate production which cost Woods the then handsome fee of nearly 60 pounds (about $NZ9000 in today’s currency).

The song continued to grow in prominence and popularity. When Woods wrote, “I immediately felt like one inspired,” he was undoubtedly describing God’s anointing. Astonishingly, Woods is known for no other composition. Not only was Woods the inspired composer, he was also an inspired, energetic and diligent promoter. He always published and promoted the song as “National Anthem,” even although it had no official recognition as such. What motivated Woods to do this? There are two possibilities: Woods was ambitious about promoting his song; or, he had a “God sense” about the song. I believe the latter is certainly true. Woods was prophetically declaring that which was already predetermined in the heart of God.

The Initial Public Reaction

Woods sought Bracken’s expert advise on how to distribute the song. Copies were sent to schools, to people of note, and to newspapers throughout the country. Glowing reviews started coming forth.

“The music is well adapted for school singing. It is to be desired that this should become the National Song of our adopted country. It is worthy of note that New Zealand was the first colony in the British Empire to evince a truly national spirit in song…Simplicity, a child of two years old sang it” Sir George Grey (11th Premier of New Zealand).

“The music has the merit of simplicity and sweetness and is well adapted for singing in chorus, which is one of the chief requisites of a national anthem. The words are stirring and appropriate” Auckland Star (18th June 1878).

“The ode is spiritedly written, and no doubt will become as popular here [Christchurch] as it has in Dunedin” Globe (14th June 1878).

“It is utterly void of “blow” [boasting/bragging] or vulgarity of any kind; and consists merely of such a prayer as a young, vigorous and earnest community might be supposed collectively to offer to the only Ruler of Princes who from His throne beholds all the dwellers upon earth” Timaru Herald (14th June 1878).

The review from Mercury, a newspaper from Woods’ home town of Hobart, Tasmania was particularly prophetic:

“New Zealand has secured what promises to be not a mere ephemeral substitute but a lasting National Anthem, of which it may be proud…we predict a lasting fame for it and have no doubt it will be amongst the music of the future” (25th September 1878).

In a private letter to Woods, William Swanson, MP for Newton, made the following insightful comments:

“We came to this Colony from many lands in which there are old sores, and interested parties here wish to keep them open, so that their own ends, and at their own times, one set of colonists may be played off against another. Having a knowledge of this, my firm conviction is that the man who will produce a song…which the children of our schools will take pleasure in singing, and that will be spontaneously sung on great occasions, will have done more to mould them into a people with brotherly love for each other, and objects in common, than the preacher of thousands of sermons, or the maker of any number of laws” (23rd November 1878).

The Māori Translation

Woods enquired of Sir George Grey about the possibility of the words being translated into Māori. This was subsequently arranged. The Advertiser printed the words in Māori for the first time. The preamble read:

“The following is the New Zealand National Anthem in Māori dress, as translated by Mr Thomas H. Smith of Auckland, at the request of Sir George Grey. In explanation of the title, we may state that ‘Aotearoa’ is the old and poetic name given to New Zealand by those who first saw it, when coming from the distant isles of the Pacific, the cradle of the Māori race, and means ‘The Long White Cloud’ or ‘The Cloud of Dawn’” (26th October 1878).

From Unofficial to Official National Anthem

Not only did the song garner glowing reviews, it was regularly sung in primary schools and public functions throughout the country, particularly in Otago. A second edition was published in 1882, this time printed in New Zealand. For the next forty years these two editions were the only printed copies available. Many New Zealanders from this period remember singing the song at morning assembly around the school flagpole.

Despite the enthusiasm that surrounded the song it didn’t officially become New Zealand’s National Hymn until 1940. Even then, it wasn’t until 1977 that it officially joined “God Save the Queen” as New Zealand’s second National Anthem. Most New Zealanders don’t even know that “God Save the Queen” is still an official New Zealand National Anthem.

Bracken and Injustice Against Māori

The words of “God Defend New Zealand” give insight into Bracken’s heart. To appreciate the full meaning and intent of his words, however, requires some extra digging. Bracken was always quick to come to the defence of the oppressed and the downtrodden. Of particularly note is his heart toward Māori and his interest in Māori affairs. To understand his heart more fully we will examine (i) the words of “God Defend New Zealand”; (ii) the content and masthead of the Advertiser; (iii) Bracken’s poem “Orakau”; and, finally, (iv) Bracken’s time in parliament.

(i) The Words of “God Defend New Zealand”

“Pacific’s Triple Star”

The first verse of “God Defend New Zealand” includes the words, “Guard Pacific’s triple star, from the shafts of strife and war.” When Bracken wrote this line he most likely had in mind the then recent conflicts of Māori and Pākehā known today as the New Zealand Wars (1845-1872). There are several reasons why it is unlikely that “the shafts of strife and war” refer to foreign invasion.

- The context of the first verse.

The prior phrase, “in the bonds of love we meet,” suggests a local context. - The subject of the third verse.

The third verse deals very specifically with the possibility of foreign invasion. - Word use in New Zealand.

At the time the word “war” was more commonly used about local, rather than international, conflict.

There is much conjecture on the meaning of “Pacific’s triple star,” but the use of the term in a prayer with allusions to Māori Pākehā conflict does imply special significance. Two flags of Māori war leader, Te Kooti, had three stars on them. Eminent historian, Judith Binney, affirms that the three stars on Te Kooti’s flags symbolise the three main islands of New Zealand—North Island, South Island and Stewart Island. The Māori King movement (Kīngitanga) also had flags with three stars, or three symbols, known to represent the three main islands of New Zealand.

It is hard for us to appreciate the huge significance both Māori and Pākehā placed on flags in New Zealand’s early history. In his 1890 poem, “Jubilee Day,” Bracken mentions the “war-torn standard” of the “Starry Cross” flying together with the “British Banner.” Most likely the “British Banner” refers to the Union Jack and the “Starry Cross” refers to a Māori flag which had three stars and a cross.

Unfurl our stainless flag and let it wave [Union Jack]

Beside the war-torn standard of the brave, [Māori flag]

Together let them gaily float and toss

The British Banner and the Starry Cross.

Let them kiss the cheerful breeze

That fans the islands of the sunny seas

These silken symbols of the New and Old

Have fame and honour traced on every fold.

Pacific’s triple star. Three simple words. Several layers of meaning. It goes without saying that poets love phrases that have layers of meaning—subtle, or not so subtle.

(ii) The Advertiser

In Search of Treasure

Eager to find out more I went in search of treasure. Fortunately I live in Dunedin so I visited the Dunedin Public Library. I was hopeful the library would have copies of the Advertiser in its archives. Unfortunately the library’s copies of the Advertiser had been sent away to be scanned by New Zealand’s national newspaper archive. They did, however, have a very fragile bound volume that contained the first six months of the Advertiser (July-December 1875). It had been presented to the eighth Premier of New Zealand, Sir Julius Vogel, and was signed by Bracken himself. The librarian retrieved it from their basement archive, and, despite it’s “Very Fragile” classification, graciously allowed me to view it. I was able to photograph the masthead and some of the content of the paper.

The Content of the Advertiser

As I perused through the volume a couple of headings caught my attention. The first one read, “MAORI PROVERBS” (7th August 1875); the second one, “MAORI PROVERBS AND SAYINGS” (21st August 1875). Both headings were followed by various proverbs and sayings with some brief explanations of their meanings. On further research I discovered that the two items were reprinted from the Waka Maori newspaper (6th July 1875, 3rd August 1875). The only other New Zealand newspaper to reprint the first item was the Thames Advertiser (20th November 1875). The second item was reprinted in no other newspaper except Bracken’s Advertiser. Bracken’s inclusion of these items does hint at a genuine appreciation for Māori wisdom and a desire to share the treasures hidden in Māori culture with his contemporaries. A fuller examination of his life makes these conclusions even more certain.

The Masthead of the Advertiser

The mastheads of modern newspapers convey little about the actual content or philosophy of the newspaper. Mid-Victorian newspapers, on the contrary, used rich symbolism in their mastheads. The masthead of the Advertiser showed Captain Cook at the centre.  On the left was a chiefly Māori figure. Further to the left was a long flag with two crosses and a heart. To the right of Captain Cook was a bearded settler. Further to the right was a long flag with a Union Jack and four stars.

On the left was a chiefly Māori figure. Further to the left was a long flag with two crosses and a heart. To the right of Captain Cook was a bearded settler. Further to the right was a long flag with a Union Jack and four stars.

The flag on the left is reminiscent of the flags of the Māori King movement and the flags of Te Kooti, though not identical with any of them. The imagery of Māori Pākehā partnership is clear. Both races are equally acknowledged. Maori, as the original occupants of the land, are given pre-eminence by being on the left.

(iii) "Orakau"

As already mentioned, Bracken’s “National Hymn” has first place in his poetry collection, “Flowers of the Free Lands.” Interestingly, the fourth poem in the collection is called “Orakau.” This poem gives remarkable insight into Bracken’s admiration of Māori. Ōrākau was a fortified Māori pā built by Waikato chiefs. The Māori land of Waikato had been taken by government forces. Ōrākau was the last major battle of the Māori Kingite forces before retreating to the rugged King Country. Bracken’s poem is about the legendary battle fought between British troops and Kingite forces in April 1864. The battle was fought over a three day period.

By the third day of the siege the pā was surrounded by 1800 British troops. Inside the pā were a few hundred courageous Māori, including women and children. Their situation was desperate. They were short of ammunition and had run out of drinking water. The British commander, impressed with the courage of the Māori warriors, ordered a cease fire and gave them the opportunity to surrender. Ngāti Maniapoto chief, Rewi Maniapoto, responded:

“Ka whawhai tonu ahau ki a koe, ake, ake.”

“I shall fight you forever, and ever, and ever.”

Hearing the resolve of the Māori warriors the British offered for the women and children to leave the pā. Before Rewi had a chance to respond, Ahumai Te Paerata, daughter of a Taupō chief, stood and cried out:

“Ki te mate nga tane, me mate ano nga wahine me nga tamariki.”

“If the men die, the women and children must die also.”

The negotiations ended and the siege continued. Once the walls of the pā were breached most of the occupants fled with the British in hot pursuit. Sixteen British troops died in the battle. Estimates of Māori fatalities range from 80-160.

Bracken’s poem praises the bravery of the Māori warriors:

“Oh, never in the annuals of the most heroic race,

Was bravery recorded more noble or more high.”

Bracken’s poem “Orakau” shows both his awareness of Māori issues and his admiration for Māori. It was first published in the Advertiser on 22nd July 1876. It is significant that his “National Hymn” was written in the same period. The song competition for the “National Hymn” appeared in the Advertiser in the three weeks prior to “Orakau” (July 1st, 8th, 15th). In Bracken’s preface to “Flowers of the Free Lands” he reveals his heart and motivation for writing both of these poems:

“Poetry has been a kind preceptress [instructor] to me since my boyhood. I have loved her for the lessons which she taught me; and, though not indifferent to poetic fame—shadowy though it be—I have poured forth my freshest emotions in song, because I found it the most congenial way of expressing what I felt. The Flowers which I now offer...have sprung spontaneously from the garden of the heart...I present them as they are, with affection and devotion, to the dear Free Lands where I have passed the best portion of my life” (1st January 1877).

When Bracken felt strongly about something it poured out of him through his poetry. That’s why both “National Hymn” and “Orakau” give us profound insight into his heart. In fact “Orakau” shines a light on “National Hymn” that helps us interpret the hymn’s full force and understand some of its hidden nuances.

In studying Bracken’s poem “Orakau” I made a curious discovery. The poem appears in four of Bracken’s collections published during his life time:

- Flowers of the Free Lands (1877).

- Lays of the Land of Maori and Moa (1884).

- Musings in Maoriland (1890).

- Lays and Lyrics: God’s Own Country and Other Poems (1893).

“Musings and Maoriland” and “Lays and Lyrics” have a significantly longer version of the poem. Some time between 1884 and 1890 Bracken added to and reworked the poem. It seems that the Battle of Ōrākau continued to occupy Bracken’s mind even after writing the original version of the poem in 1876.

(iv) Bracken’s Time in Parliament

In 1881 Bracken was elected as the Member of Parliament for Dunedin Central. 1881 was also the year that government forces brazenly invaded and dispersed the people of the Māori village, Parihaka. The two chiefs, Te Whiti and Tohu, were imprisoned indefinitely without trial. Bracken vehemently disagreed with this action. He boldly confronted Native Minister, John Bryce:

“Are we living in a free British colony, or under some petty local despot? Will the people of New Zealand allow any man, even though he hold the rank of Native Minister, to ride roughshod over the constitution? Will they allow any man, even though he be a Minister of the Crown, to suspend trial by jury if it so pleases him?...If they are entitled to the rights and privileges of British subjects, they are entitled to the right of trial by jury...I stand here to protest, although I may be the only one in the House to do so, against this un-English proceeding on the part of the Ministry” (Hansard 1882 Vol. 41 p. 118-119).

Bracken agreed with some of the other members of the House that Te Whiti should be allowed to testify in parliament:

“We do not want to hear only a one-sided statement...There was a time in the history of New Zealand when the Maoris, if they had chosen, could with one swoop have swept the European race from this Island. That time was the time of the Treaty of Waitangi. What did they do then? You call them savages, barbarians; but they treated us in a way that should make us blush in our conduct to them...I feel very strongly on this matter, and I appeal once more to the sense of justice of the honourable gentlemen on those benches to accede to this little request, and not allow the finger of scorn to point for all time at this honourable House and this adopted country of our race.” (Hansard 1882 Vol. 41 p. 266).

After being elected to Parliament Bracken declared, “I am tied to no Party and I will work for all classes—for justice for all.” He lived up to his claim.

“Poisoned Shafts” and “Bonds of Love”

Bracken was an orphan. He had seen his Irish kinsfolk devastated by the Great Famine of 1845-1849. He had been uprooted from his native country. He had experienced the pain of rejection after being disavowed by the Catholic Bishop of Dunedin—also one of his kinsfolk. He experienced political defeat in 1879 and 1884. Throughout his life Bracken struggled to find where he really fitted. Bracken’s tumultuous life story and his sensitive heart enabled him to both identify with, and empathize with, Māori. His contribution to public life was significant. His greatest legacy, a song.

Financial difficulties in the latter part of his life left him impoverished. Although this was partly due to Bracken’s mismanagement of funds, it was also largely due to consequences he bore for making principled stands. His latter years were marked by a vulnerability to alcohol. He died of a large goitre on the 16th of February 1898 at the age of 56. Bracken went from being very much in the public eye to being largely hidden and unnoticed. The popularity of his poems lived on for several decades after his death. Bracken’s vision for his adopted nation is encapsulated in the first two lines of “God Defend New Zealand”:

“God of nations! at Thy feet

In the bonds of love we meet.”

When Bracken died he was more familiar with “poisoned shafts” than “bonds of love.” Regardless, God arranged that Bracken’s vision would live in the hearts of Kiwis for all generations.

A time will come when the words of “God Defend New Zealand” and its status as New Zealand’s National Anthem will be challenged. During his life time Bracken stood in defence of Māori concerning injustices against them. When the status of Bracken’s “National Hymn” is challenged, Māori will rise in its defence. New expressions of the National Anthem will come forth that will carry the depth, the strength and the ferocity of a Māori war cry. This will give birth to totally new creative expressions—songs, poems, dance, art—that will carry the spirit and cry of Bracken’s words and release God’s heart for Aotearoa. The old and the new will come together. Foundations will shake. A new era will be birthed.

A Gift to the Nation

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840. God knew that the treaty would be dishonoured and that deep wounds would infect the relationship between Māori and Pākehā. For Māori the hope and promise of the early years gave way to betrayal and despair. Despite the multiple human failings, God was far from inactive. When the time came He breathed on a poet and a composer. Inspiration gave birth to a song. The song gave expression to a new hope—a hope that still resonates over Aotearoa.

God-breathed inspiration lifts words out of their contemporary context and gives them lasting permanence. “God Defend New Zealand” is more than just a song. It is a gift from God to the nation. From the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi to the writing of “God Defend New Zealand” was a short period of time—thirty six years to be exact. New Zealand was still a young nation. Despite her youth she had already experienced painful internal conflicts and wars. “God Defend New Zealand” expressed the heart of God and prophesied over the wounded nation.

Multitudes of Māori and Pākehā from up and down the nation sung the prayer. It resonated with destiny. It carried God’s anointing. It established identity. Some sung it simply as Kiwis, proud of their national identity. Others sung it as intercessors, calling forth a new dawn. Either way, the words ascended as a sweet smelling aroma before the throne of God. The song is a declaration and a prayer. Ultimately it came from the heart of God. Continually it ascends back to Him.

Every utterance adds weight...

and beauty...

and glory...to the answer.

And it is a prayer that will be answered.

© 2020 Nathan Shaw. All Rights Reserved.

Related Articles:

"God Defend New Zealand" & "Orakau" – Thomas Bracken

"Not Understood" – Thomas Bracken

Bibliography

Books

Binney, Judith, Redemption Songs: A Life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki

Auckland University Press & Bridget Williams Books, 1997, Plates 6 & 7

Bracken, Thomas, Behind the Tomb and Other Poems, 1871

Bracken, Thomas, Pulpit Pictures, 1876

Bracken, Thomas, Flowers of the Free Lands, 1877

Bracken, Thomas, Lays of the Land of Maori and Moa, 1884

Bracken, Thomas, Musings in Maoriland, 1890

Bracken, Thomas, Lays and Lyrics: God’s Own Country and Other Poems, 1893

Cryer, Max, Hear Our Voices, We Entreat: The Extraordinary Story of New Zealand’s National Anthems

Exisle Publishing Limited, 2004

Heenan, Ashley, God Defend New Zealand: A History of the National Anthem

School of Music, University of Canterbury, 2004

Jones, Jenny Robin, Writers in Residence: A Journey with Pioneer New Zealand Writers

Auckland University Press, 2004, Chapter 10

Newman, Keith, Beyond Betrayal: Trouble in the Promised Land – Restoring the Mission to Māori

Penguin Group, 2013, Chapter 16

Templeton, Hugh; Templeton, Ian; Easby, Josh, Speeches That Shaped New Zealand 1814-1956

Hurricane Press Ltd, 2014, Chapter 7

Magazines

Andrews, Colin, Triple Star Study: God Defend New Zealand and The Meaning of ‘Triple Star’

The Volunteers, Journal of New Zealand Military Historical Society (NZMHS)

Vol. 26, No. 2, Nov. 2000, p. 104-109

Walker, Peter, Who’s the We? Maori, Pakeha and an anthem’s bonds of love

North & South Magazine, April 26th 2017

Online Sources

Catholic Parish Registers at the NLI

(https://registers.nli.ie)

Thomas Bracken Sr & Margaret Kiernan Marriage (4th September 1840)

Dunboyne, Microfilm 04176 / 05 p. 65

Thomas Bracken Jr Baptism (30th December 1841)

Dunboyne, Microfilm 04176 / 08 p. 88

Margaret Kiernan Death (8th December 1846)

Dunboyne, Microfilm 04176 / 04 p. 68

Thomas Bracken Sr Death (August 1852)

Dunboyne, Microfilm 04176 / 04 p. 73

New Zealand Census Data

1874 Census

1878 Census

Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand

(https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz)

Auckland Star (Auckland)

Globe (Christchurch)

Saturday Advertiser (Dunedin)

Southland Times (Invercargill)

Thames Advertiser (Thames)

Timaru Herald (Timaru)

Waka Maori

Parliamentary Debates (Historical Hansard)

(www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/historical-hansard)

1882, Vol. 41 p. 118-119, 266

Reserve Bank of New Zealand Inflation Calculator

(www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator)

NB: One guinea is worth one pound one shilling. £1.05 using decimal values.

Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

(www.teara.govt.nz)

Broughton, W. S. 'Bracken, Thomas', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993, updated May, 2014

Wikipedia

(www.wikepedia.org)

God Defend New Zealand

Great Famine (Ireland)

Invasion of the Waikato, sub-section: Ōrākau

Thomas Bracken

WikiTree

(www.wikitree.com)

Thomas Bracken (1811)

Margaret Kiernan (abt. 1820-1846)

Thomas Bracken (1843-1898) NB: Official records show that Bracken was born in 1841, not 1843, and that his parents church association in Ireland was Catholic, not Protestant (see Catholic Parish Registers at the NLI listed above)

Back to Words for Nations